Rates of workplace violence experienced by women are on the rise in Ontario’s education sector, making them four to six times more likely than their male counterparts to require time off work due to physical assaults on the job.

This is according to a study by the Institute for Work & Health (IWH), published in the January 2019 issue of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (doi:10.1136/oemed-2018-105152). The study drew on about a decade’s worth of data (up until 2015) from two population-based sources: the number of lost-time claims due to assaults accepted by Ontario’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) and the number of emergency room (ER) visits across all Ontario hospitals due to assaults at work.

In Ontario’s health-care sector, the study found men are almost twice as likely as women to have lost-time workers’ compensation claims due to assaults. However, the study also showed rates of workplace violence declining more sharply among men than among women over the timeframe examined, thus narrowing the gender gap in the health-care sector.

Outside the health-care and education sectors, the study found the much lower risks of workplace violence to be similar for men and women.

When it comes to workplace violence, our research suggests that the differing risks among men and women depend on sector and type of violence,

says IWH Senior Scientist Dr. Peter Smith and principal investigator on this research project.

Our research also found that the rates of workplace violence among men and women are changing over time,

adds Smith, who holds one of nine Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) research chairs in gender, work and health. Data from both the province’s workers’ compensation board and hospital emergency departments indicate that workplace violence is stable among men and increasing among women.

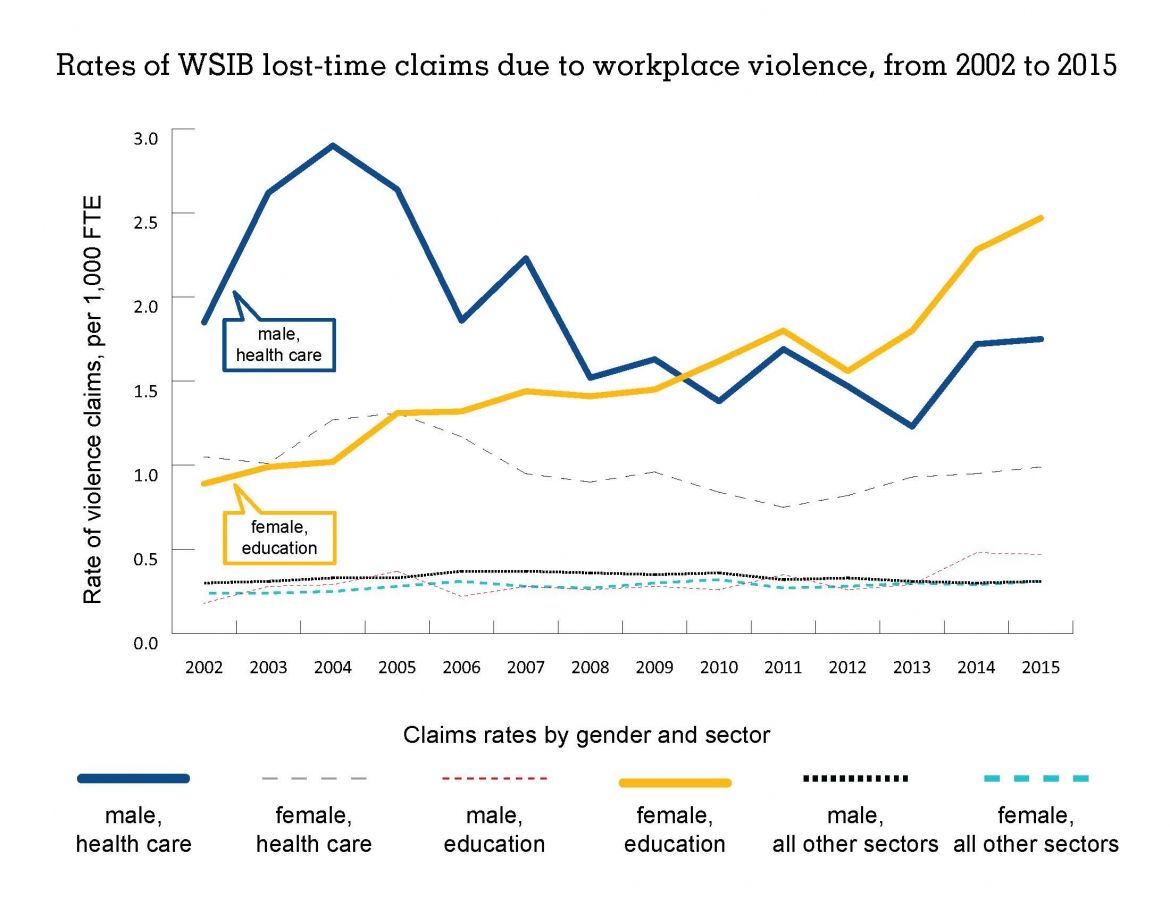

Although workplace violence prevention efforts in recent years have tended to focus on health-care workers, the risk of experiencing violence has been rising for over a decade among women in education—now surpassing absolute risk levels for both men and women in health care, notes Smith (see the graph below).

Two population-based sources

To conduct the study, the research team looked at WSIB lost-time claims attributed to workplace violence from 2002 to 2015, as well as the number of emergency room visits across all Ontario hospitals from 2004 to 2014 due to assaults at work. (Since 2000, it has been mandatory for all hospitals in Ontario to report to a national database on the number and nature of ER visits, including whether visits are due to work-related injuries or illnesses—regardless of whether these injuries or illnesses would be accepted by a workers’ compensation board or not.)

Based on the WSIB lost-time claims data, the research team noted marked differences between men and women in two sectors: education and health care. In education, rates of lost-time claims related to violence climbed for women—from 0.89 per 1,000 full-time equivalent employees FTE in 2002 to 2.47 per 1,000 FTEs in 2015. In comparison, rates of violence-related claims among men in education rose from about 0.18 per 1,000 FTEs in 2002 to 0.47 in 2015.

Rates of violence-related claims among men in health care went down from 1.85 per 1,000 FTEs in 2002 to 1.75 in 2015. Rates also declined for women in health care, from 1.05 to 0.99 per 1,000 FTEs over the same time period.

With respect to rates of workplace violence across all sectors, violence-related WSIB claims among men remained relatively stable, ranging around 0.3 to 0.4 per 1,000 FTEs. Over this same period, rates for women increased from 0.4 per 1,000 FTEs in 2002 to 0.64 per 1,000 FTEs in 2014. Although lost-time claim rates for women were consistently higher than for men, the difference between them also widened during the study period. In 2002, women had 30 per cent more lost-time claims than men; by 2015, they had 86 per cent more.

When it came to hospital ER records, the study team found men had slightly higher rates of ER visits than women, though that difference narrowed over the study period. In 2002, rates of visits were 0.28 per 1,000 FTEs among men and 0.20 per 1,000 FTEs among women. By 2014, rates for both men and women stood equal at 0.27 per 1,000 FTEs, confirming the trend seen in the WSIB data of women experiencing more workplace violence.

Cynthia Chen, an IWH research associate and lead author of the journal article, offers potential reasons why the two datasets show different patterns of reporting between men and women. It may be that acts of aggression experienced by men are more likely to result in severe injuries that require emergency department treatment,

she says. As well, it could be that a proportion of WSIB claims do not require emergency department treatment, but still result in time off work due to their psychological consequences.

Although the two data sources pick up different rates of violence, what’s key is that both are showing an increase among women,

Chen says.

This study reinforces the need for better records on workplace violence, says Smith. Although the sources used in this study represent some of the best available data we have at the population level, the vast difference between the two highlights the need for a surveillance system across the country. That’s something researchers and prevention stakeholders have been calling for, for many years,

he adds. If we want to get serious about addressing workplace violence, we need first to understand how much violence is occurring. If we don’t, how can we know if our efforts are effective?