In 2019, two years after the Ontario government’s training standard on preventing falls from heights came into full effect, a study found construction workers continued to maintain the safer practices that they had adopted soon after their training in 2017.

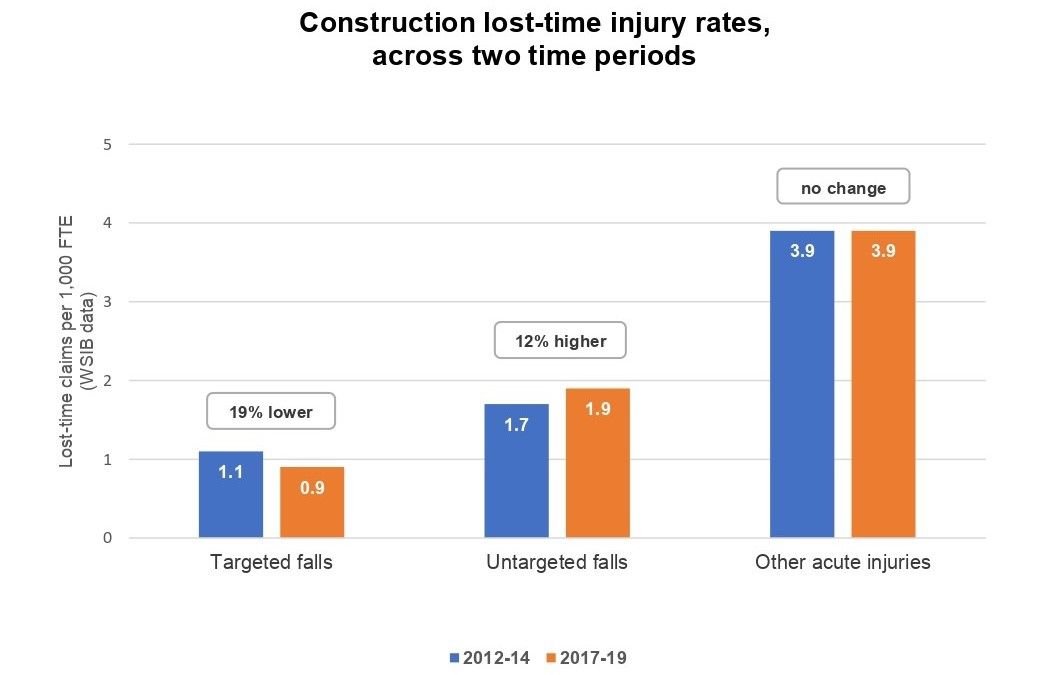

Importantly, the study conducted by the Institute for Work & Health (IWH) also found a 19 per cent decline in the rate of injuries caused by the types of falls that were targeted by the training standard. That’s based on a comparison of lost-time injury rates between the three-year period of 2012-2014 and the three-year period of 2017-2019. That decline translated to about 320 fewer injuries due to falls from heights in 2017-2019.

To put that decline in context, during that same time frame from 2012-2014 to 2017-2019, other types of work-related injuries either underwent an uptick in incidence rate or remained unchanged: types of falls not targeted by the training (for example, falls down stairs or falls from the same levels) rose by 12 per cent; other types of acute injuries remained the same.

What’s more, the decline in injury rates of targeted falls in Ontario was notably larger than that seen in other provinces. The corresponding decline in the other Canadian provinces over the same time period was six per cent, a much smaller decline than the 19 per cent seen in Ontario,

says Dr. Lynda Robson, IWH scientist and lead researcher on the project. An article about this study was published in November 2023, in the American Journal of Public Health (doi:10.2105/AJPH.2023.307440).

A decline of 19 per cent may appear modest, but from what we’ve seen in other occupational health and safety training research, that percentage change in outcome is what we would expect from well-planned training programs,

adds Robson, who also shared the findings at an IWH Speaker Series webinar in December. In summary, the province has achieved about all it can achieve through working-at-heights training alone. We encourage other ongoing efforts to prevent falls from heights in the province’s construction sector.

Two-year follow-up

This study was a follow-up to a 2017 study, which examined the effectiveness of the training standard in the immediate aftermath of its implementation.

In that study, Robson and her research team found a 20 per cent decline in falls targeted by the training between 2012-14 and 2017. They also found that the mandatory training had high uptake across the province and led to changes in safety practices among employers and workers. That study used six different sources of data, including administrative records on training uptake from the Ontario Ministry of Labour, Immigration, Training and Skills Development, as well as lost-time claims data from the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board. That study also included a survey of training providers, a survey of employers and interviews with labour inspectors.

The centrepiece of that study was a survey of about 600 workers who took the training provided by the Infrastructure Health & Safety Association (IHSA) or their training partners. The worker survey was conducted at three different intervals: the first at one week after the training (which asked about work practices two weeks before training), then again at four weeks and seven weeks post-training.

In this latest study, the team went back to the workers who were surveyed following their training in 2017 and asked them to do a two-year follow-up. Almost 300 workers took part in this 2019 survey. They were asked to take a 10-question knowledge test—the same test given to them at the start and at the end of their training day in 2017. A large initial knowledge gain had been observed, with the average score rising from 6.8 (out of 10) in pre-training tests to 9.5 immediately post-training. Two years later, the average score was 7.5—a decline, but still a gain compared to the pre-test score, notes Robson.

Moreover, when the research partners at IHSA looked at which knowledge items had eroded the most, these tended to relate to questions about regulation and policy. On questions related to on-the-job knowledge, such as what types of ladders to use or what “bottoming out” means, the scores indicated that knowledge improvement was retained.

The surveyed workers were also asked about the extent to which they followed 12 safety practices—for example, checking sites for hazards, inspecting fall protection equipment or maintaining 100 per cent tie off. When we compared practices at four weeks after the training with pre-training practices, for 10 out of the 12 work practices there was a statistically significant change toward greater safety. In many cases it was a meaningful change,

says Robson.

Two years later, there was no slippage or erosion of those improvements in safety practice. The extent to which workers said they followed safety habits held up two years after.

In both studies, the one conducted in 2017 and the follow-up study, the research team examined lost-time claims data to see whether the change in work practices was associated with lower injury rates. Lacking a comparison group in the first study, the team used claims rates for other types of injuries in construction: falls not targeted by the training standard and other acute traumatic injuries.

The purpose of having these two categories of comparison was to pick up on other changes happening in the environment that could impact injury rates,

says Robson. That is, if the intensity of work in construction changed over time, or if the adjudication of claims by the workers’ compensation agency changed in a systematic way over time, for example, these comparator injuries would pick up on those changes and thus provide a type of control for our targeted falls data.

In the latest study, the team had an additional source of comparator data. These were lost-time claims rates for the same categories of injuries from all other provinces. “Importantly, we saw a big difference in incidence rate ratio for targeted falls,” she notes. Whereas Ontario saw a 19 per cent decline in the incidence rate of targeted falls, that incidence rate in the other nine provinces fell by only six per cent. (As for the two other categories, rates of untargeted falls rose by four per cent in the other nine provinces, compared to 12 per cent in Ontario; rates of other acute injuries fell by four per cent in the other provinces, compared to no change in Ontario.)

That suggests something special was going on in Ontario with respect to targeted falls. It’s consistent with the training standard introduced in Ontario being effective,

she adds. Yes, we see some change in other provinces, too, but falls from heights were the focus of ongoing effort in all provinces. What's notable is the difference between the 19 per cent decline and the six per cent decline.

Number one cause of deaths

Falls from heights are the number one cause of traumatic fatalities and a major cause of non-fatal injuries in construction. According to data from the CPWR, a construction safety research centre based in Silver Spring, Md., the top three sites of fatal falls from heights are roofs, ladders and scaffolds or staging.

In 2015, following a recommendation by an expert advisory panel on Ontario’s health and safety system, the province introduced a mandatory working-at-heights training program that was standardized and to be delivered only by accredited training providers. Although training had been mandatory since 2001, the introduction of a training standard and an accreditation process for providers represented quite a shift in the prevention of falls from heights,

says Robson.

Indeed, surveyed workers in the recent study tended to support the training standard. They were asked, based on their experience over the past five years, whether the mandatory working-at-heights training had made working at heights on construction projects safer. Ninety per cent said definitely or probably yes—a very strong endorsement,

says Robson—while only five per cent said definitely or probably no.