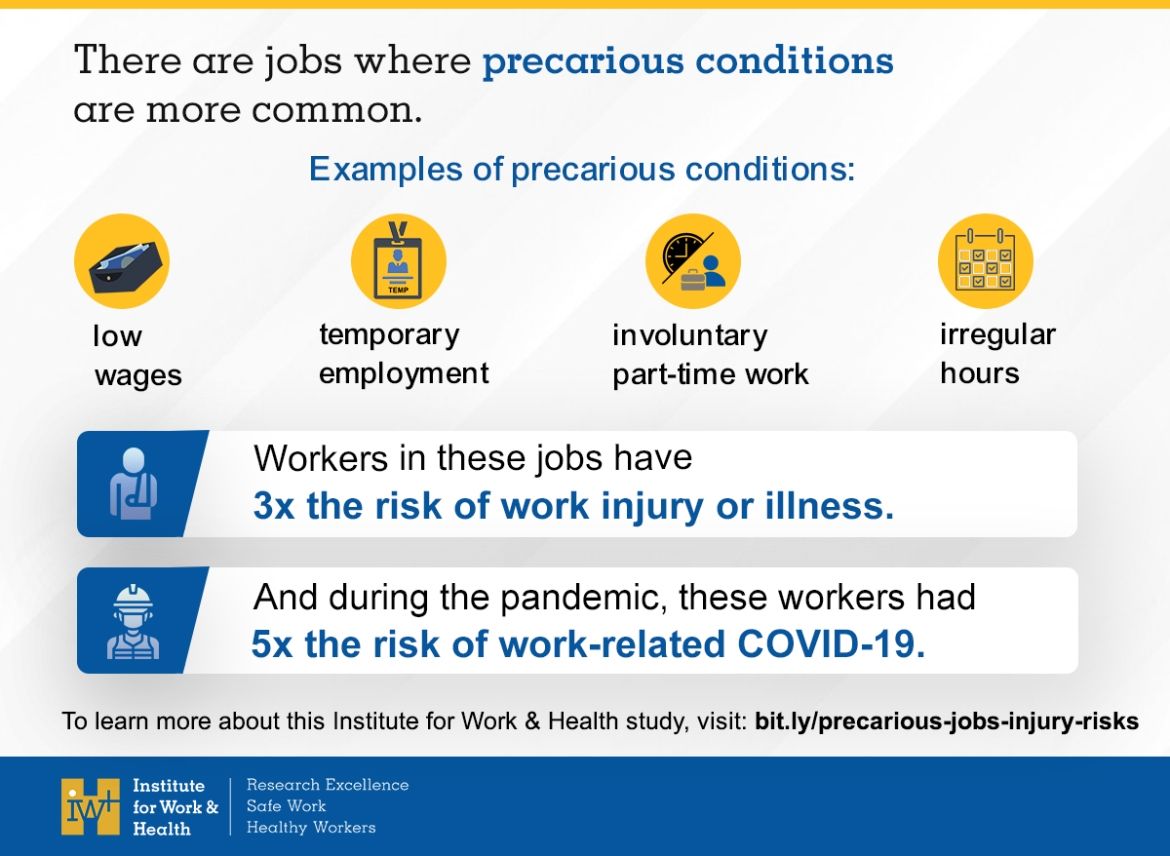

Workers in jobs where precarious employment conditions are more common are more likely to experience a work-related injury or illness, including COVID-19, in Ontario.

That’s according to a pair of studies authored by Institute for Work & Health (IWH) researchers that examined whether employment conditions other than physical hazards may be linked to the rate of work injuries.

When we think of work injuries, we tend to think about factors in the immediate work environment that lead to harm, like a tripping hazard or unsafe equipment,

says Dr. Faraz Shahidi, IWH associate scientist and lead on the studies. While these aspects of the work environment are important to consider, there are also broader employment conditions of a given job that may shape a worker’s risk of falling ill or getting injured at work.

Jobs with unfavourable employment conditions are often called “precarious” jobs. These jobs are characterized by temporary contracts, part-time hours, irregular schedules and low wages.

Precarious jobs are not uncommon in Ontario

, says Shahidi. Workers who lack stable, secure employment, or a union to protect them, might hesitate to report unsafe working conditions or refuse unsafe work, in case it costs them their job. Low wages might push workers to hold multiple jobs, work longer hours, or be willing to accept more dangerous work to make ends meet.

The first study, published in Occupational and Environmental Medicine (doi:10.1136/oemed-2024-109535), found that occupations characterized by the most precarious employment conditions had almost three times the risk of work-related injuries or illnesses compared to those with the least precarious employment conditions.

In a companion study, published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (doi:10.1136/jech-2024-222373), the team also found that work-related COVID-19 infections were reported at almost five times the rate among workers in occupations more likely to be precarious relative to those in more standard and secure employment.

Our findings suggest that precarious employment acts as an upstream driver of injuries, illnesses and infections in the workplace,

says Shahidi.

Precarious employment and work injury and illness

For the first study, the researchers gathered information about workplace injuries and illnesses in Ontario between January 2016 and December 2019 from Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) compensation claims.

WSIB claims data has information about injured workers’ occupations—but not their employment conditions. To obtain data on employment conditions, the research team turned to Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey (LFS). The team drew on responses in this survey describing the following conditions:

- temporary employment (

Is your job permanent?

) - low wages (

What is your hourly rate of pay?

) - irregular hours (

Does the number of paid hours you work vary from week to week?

) and - involuntary part-time work (

How many paid hours do you usually work per week?

andDid you want to work 30 or more hours per week?

).

Based on these responses, the team classified each occupation as having low, medium, high or very high prevalence of each condition. Occupations were also grouped based on their overall level of precarity across all four of the conditions.

Combining the WSIB claims information and LFS data on the number of hours worked in the overall labour force, the research team were able to understand whether work injuries and illnesses occur more frequently in occupations where precarious employment conditions is more likely to be present.

The researchers found that jobs with high or very high levels of precarity had almost three times the risk of work injuries or illnesses compared to those with the lowest level. Compared to jobs with a low probability of precarious employment (and adjusted for age, sex and year) work injury and illness risks were:

- 105 per cent higher for jobs with medium probability of precarious employment,

- 181 per cent higher for jobs with high probability of precarious employment, and

- 182 per cent higher for jobs with very high probability of precarious employment.

To account for jobs that are inherently more hazardous, the researchers also classified each occupation as having exposure to none or to one or more of several workplace hazards or physical demands. These included dangerous chemical substances, biological agents, equipment, machinery, and so on. Even after accounting for these factors, temporary employment, irregular hours, and involuntary part-time work were still associated with a two-fold increase in injury risk for the most precarious jobs.

We’ve shown that although the differences in injury risk between groups are partly explained by differences in traditional hazardous occupational exposures, significant associations persisted for workers in occupations more likely to be exposed to precarious employment,

says Shahidi. This tells us there are other factors likely linked to precarious employment that are increasing workers’ risk of injury, after taking traditional hazards into account.

Precarious employment and COVID-19

The second study, focusing on COVID-19, was conducted in a similar way, but with WSIB claims for work-related COVID-19 infections between April 2020 and April 2022.

Like the first study, temporary employment, irregular hours, and involuntary part-time work were each associated with higher rates of work-related COVID-19 infection. Those with very high levels of precarious employment had almost five times the risk of submitting a work-related COVID-19 claim (controlling for age, sex, and pandemic wave) compared to those with the lowest levels.

When the team accounted for aspects of a job that are likely to increase the risk of COVID-19 infection—public-facing work, working in close proximity to others and working indoors—workers in occupations with very high probability of temporary employment, irregular hours, low wages or involuntary part-time still had nearly four times the risk of work-related infections.

If we want to prevent work-related harms from disproportionately affecting those in precarious jobs, one way is to improve the quality of jobs in Ontario,

says Shahidi. This could look like stronger employment protection legislation, stricter scheduling requirements or workplace policies to better address the health and safety concerns of precariously employed workers.