People who use cannabis before or at work face a significantly greater risk of workplace injury—twice as high as the risk faced by people who don't use cannabis.

Among workers who report using cannabis but not specifically before or at work, on the other hand, there was no greater risk of work injury when compared to workers who don't use. That’s according to findings from an Institute for Work & Health (IWH) study led by Associate Scientist Dr. Nancy Carnide, who shared results in an IWH Speaker Series webinar presentation in March 2022.

When we looked at the group of workers who had used cannabis at work or before work over the past year, what we saw was a doubling of risk,

says Carnide. However, the risk of workplace injury for workers who reported use in the past year, but not before or at work, was not appreciably different from that of people who didn’t use cannabis.

These findings are the latest to come out of the ongoing study, funded through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, which began a few months before the October 2018 legalization of non-medical cannabis in Canada.

Drawing on a series of surveys first conducted in June 2018 and once a year since then, Carnide’s team has set out to understand whether patterns of cannabis consumption have changed in recent years—especially consumption during or just before work.

Given the longitudinal design of the study, the team saw a good opportunity to use the data from this study to also examine the implications of cannabis use on future risk of workplace injury. Previous studies looking at this question have had mixed findings. But none of them has looked specifically at cannabis use at or before work, says Carnide.

Once we took timing of use into consideration, we saw clearly that it’s not cannabis use outside of work that poses a risk. It’s cannabis use in close proximity to work that’s linked to a higher risk of injuries,

she adds.

How the study was done

The study was conducted by recruiting workers mainly from a pre-existing panel, run by EKOS Research Associates, of 100,000 Canadians willing to participate in surveys from time to time. A small sample was also recruited via random dialing.

The first survey was completed in June 2018 by about 2,000 individuals who worked at least 15 hours a week in workplaces of five or more employees. The second survey, conducted in the summer of 2019, was completed by about 1,100 participants in the first sample plus another 3,000 newly recruited respondents. The third survey, conducted in the summer of 2020, likewise had about 4,000 respondents, including about 2,300 repeat participants.

To collect data on workplace injuries, the surveys asked whether respondents experienced an injury in the past year.

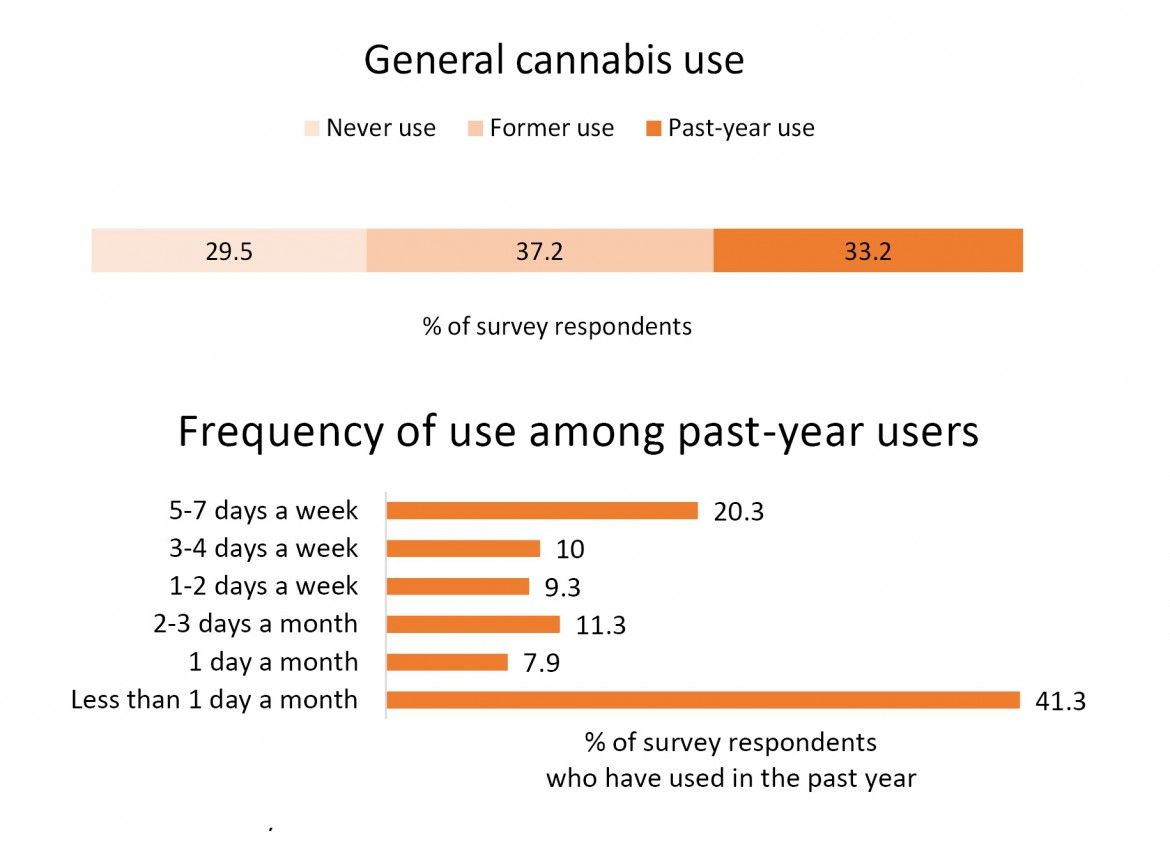

Overall, 33.2 per cent of participants said they had used cannabis within the past year. That’s slightly more than the percentage of participants who had never used cannabis (29.5 per cent) and less than those who had previously used cannabis but not within the past 12 months (37.2 per cent).

Of the participants who had used recently (within the year), the majority (41.3 per cent) used less than once a month. However, the next largest group, representing 20.3 per cent of those who used recently, consumed cannabis nearly every day.

Looking more closely at the 33.2 per cent of workers who did use cannabis in the previous year, the vast majority never used it at or within two hours before work (27.3 per cent of the overall sample). Only a very small percentage (5.9 per cent of the overall sample) reported workplace use.

Among this 5.9 per cent, 90.0 per cent said they used before work, 66.0 per cent used during work breaks, and 57.4 per cent used while working.

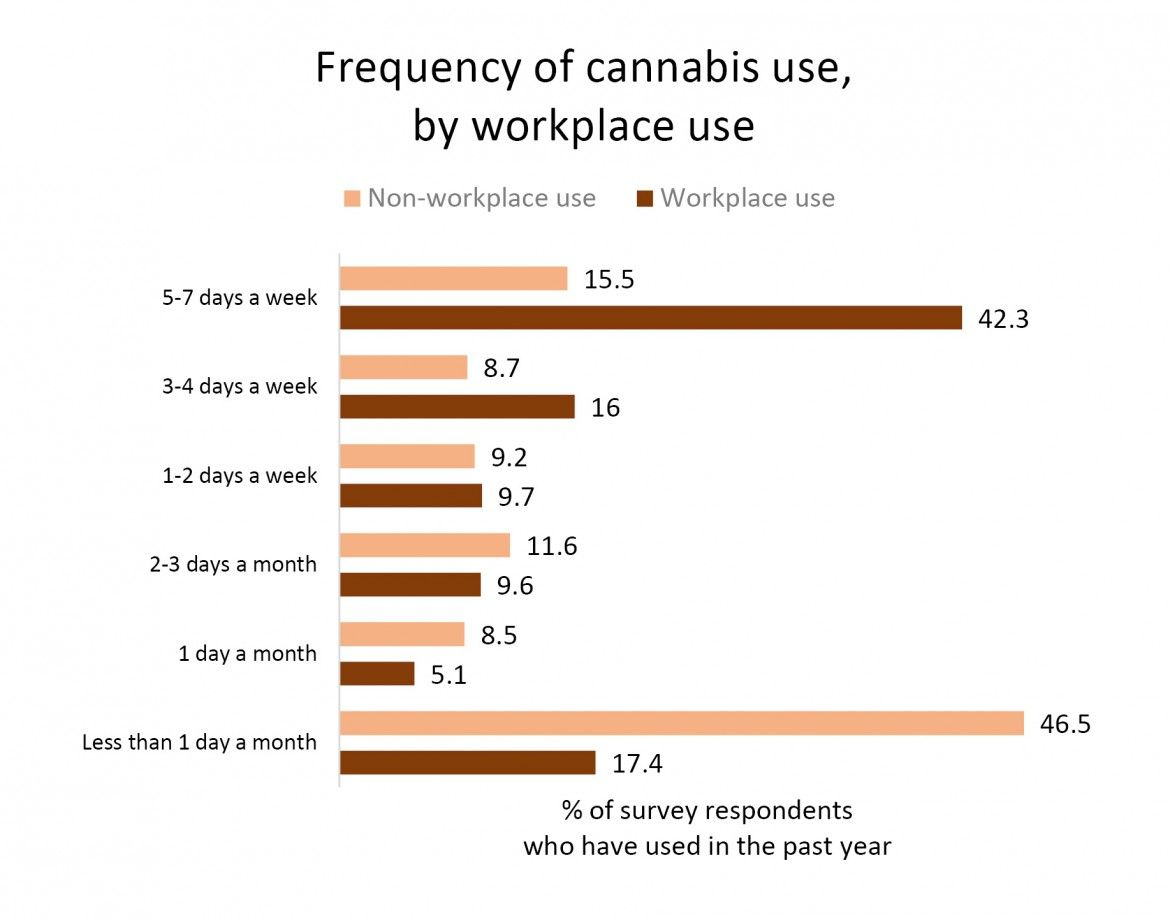

Of note was the frequency of use among workers who said they had used before or at work. Among this group, near daily use was much more prevalent. Nearly 60 per cent of the respondents who had consumed before or at work said they used cannabis throughout the week, with 42.3 per cent reporting using five to seven days a week, and another 16.0 per cent saying they used three to four days a week.

One takeaway is, generally speaking, the people who were using cannabis before or at the workplace were also the ones who were more likely to say they were using on a regular basis,

says Carnide.

Carnide acknowledges that a shortcoming of the study was its lack of information on the type and severity of injuries incurred. Another limitation was its inability to make the distinction between types of cannabis used—i.e. whether cannabis used had stronger tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or cannabidiol (CBD) content, two key ingredients determining its psychoactive effect.

An advantage of the study, as stated earlier, was its ability to tease apart people who used cannabis but not at or before work, from those who did use cannabis at or before work. Another important advantage of the study, was its ability show a link between exposure and outcome over time. The longitudinal nature of the study allows us to ensure that cannabis use preceded the injury itself,

says Carnide. In contrast, many of the previous studies examining this question were cross-sectional, where exposure and outcome were assessed at the same time.

In such studies, one cannot be sure whether the cannabis exposure preceded the injury or vice versa. This is an important limitation, because cannabis may be used by some people to manage symptoms of an injury,

Carnide adds.