Among working-age adults with arthritis in the United States, about one in eight also experience depressive symptoms, according to a new study by the Institute for Work & Health (IWH).

Having both arthritis and depressive symptoms is associated with a higher risk of work disability, particularly for people in the middle of their earning years, the study also found. For this middle-aged group (ages 35 to 54), having depressive symptoms in addition to arthritis can lower the likelihood of working by 17 per cent.

“We know from research to date that people with arthritis face challenges finding and keeping a job. We also know that depression is common among people with arthritis,” says IWH Scientist Dr. Arif Jetha, lead author of the study published in July in the journal Arthritis Care & Research (doi:10.1002/acr.24381). “This study shines a light on what having both arthritis and depressive symptoms means to people’s ability to participate in the workforce.”

The study drew on four years (2013 to 2017) of data from the National Health Interview Survey, conducted by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics. The study focused on the nationally representative sample of more than 11,000 working-age adults (ages 18 to 64) in the U.S. who reported a diagnosis of arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus and fibromyalgia).

The study found about 13 per cent of adults with arthritis also report depressive symptoms. That’s higher than the prevalence rate of five per cent of adults without arthritis who report depressive symptoms, according to an earlier analysis of the same dataset, conducted by members of the research team.

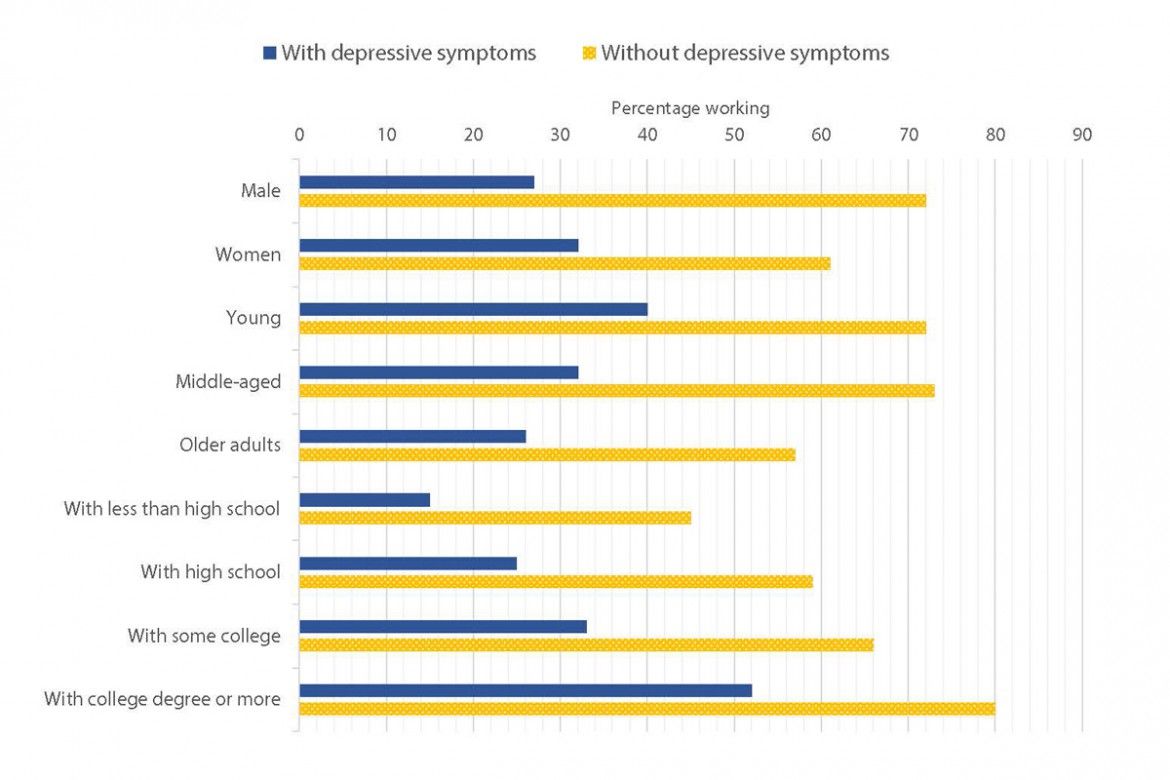

The study team compared employment among people with arthritis—with and without depressive symptoms. It found lower levels of employment in those experiencing depressive symptoms, a pattern that was consistent across different demographic, social and health characteristics (see chart).

“Because we used a nationally representative survey, the patterns of work participation we see in the study are generally representative of the adult population living with arthritis in the U.S.,” says Jetha.

Looking across age groups, the team found higher levels of employment among younger adults with depressive symptoms (40 per cent) than older age groups with depressive symptoms (32 per cent among middle-aged adults and 26 per cent among older adults).

When taking into account all other factors, the team found the adverse effect of having arthritis and depressive symptoms was strongest on middle-aged people, who were 17 per cent less likely to work than those with arthritis but without depressive symptoms. The adverse effect was only borderline significant for younger adults and not statistically significant among older adults.

“The impact that arthritis and depressive symptoms have on middle-aged people is not a surprise,” says Jetha. “The work-life balance research to date suggests that people in this age group who also live with a chronic disease tend to face challenges in engaging in multiple different roles.”

The study findings point to the need for greater access to mental health services for people diagnosed with arthritis, Jetha notes. “Given the importance of employment as a social determinant of health, these findings highlight that providing mental health care can address work disability among people with arthritis.”