About one in four young adults in the United States report persistently poor mental health in the two decades between their teenage years and their mid-30s. By the time they’re in their mid-30s, these young adults also have the lowest incomes among their same-age peers.

That’s according to a new study examining the various courses that earnings and mental health take over a 20-year span, published in January 2023 in the peer-reviewed journal, Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (doi:10.1007/s00127-022-02398).

The study was conducted by Institute for Work & Health (IWH) Associate Scientist Dr. Kathleen Dobson, as part of her PhD thesis at the University of Toronto examining the links between depression and earnings.

In an earlier paper, Dobson estimated that Canadians who experienced a depressive episode went on to earn $71,000 to $115,000 less over the next 10 years than they would have if the depressive episode had not occurred. In this new study, Dobson tapped into a rich dataset, not available in Canada, to explore a different angle. Using a 20-year dataset drawn from a large sample of American youths who were 13 to 17 years old in 1997, the study set out to examine how their mental health and earnings changed over time. It then mapped out common patterns, or trajectories, of change in earnings and mental health over a 20-year period covered by the study.

We know that common mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety disorders, can impact employment earnings and work experience. But employment earnings and work experiences can also impact the likelihood of having a common mental health disorder,

says Dobson. Little literature was available that had really looked at these two things together in a way that reflects real life. If you think about it, they’re parallel processes happening at the same time. They're not independent of each other and may be quite correlated.

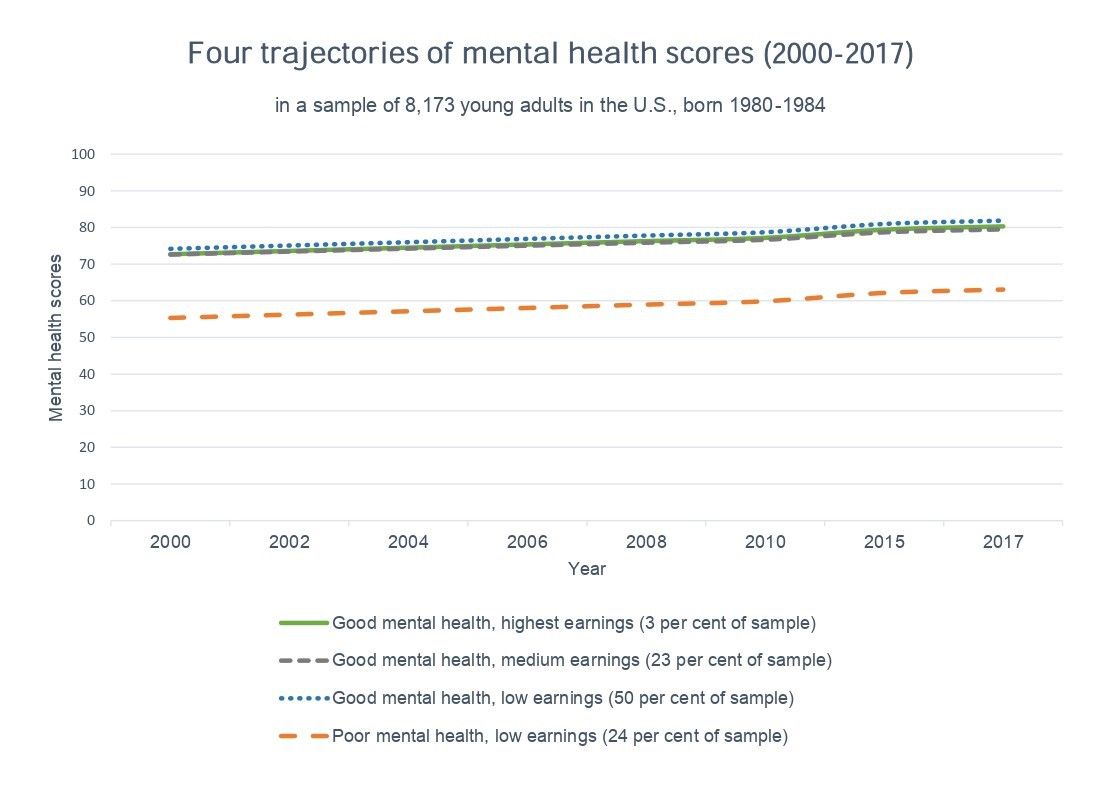

Dobson’s U.S. study found four distinct groups, defined by their mental-health-and-earnings trajectory over the two-decade timeframe. Three of the four groups had stable, positive mental health scores over the study period, indicative of good mental health. The fourth group also had stable mental health scores, but they were distinctly lower than the others. “The mental health scores of this group are in the range of what many researchers consider as cut-off scores for psychological distress or a depressive or anxiety disorder,” says Dobson. This fourth group made up about 25 per cent of the sample.

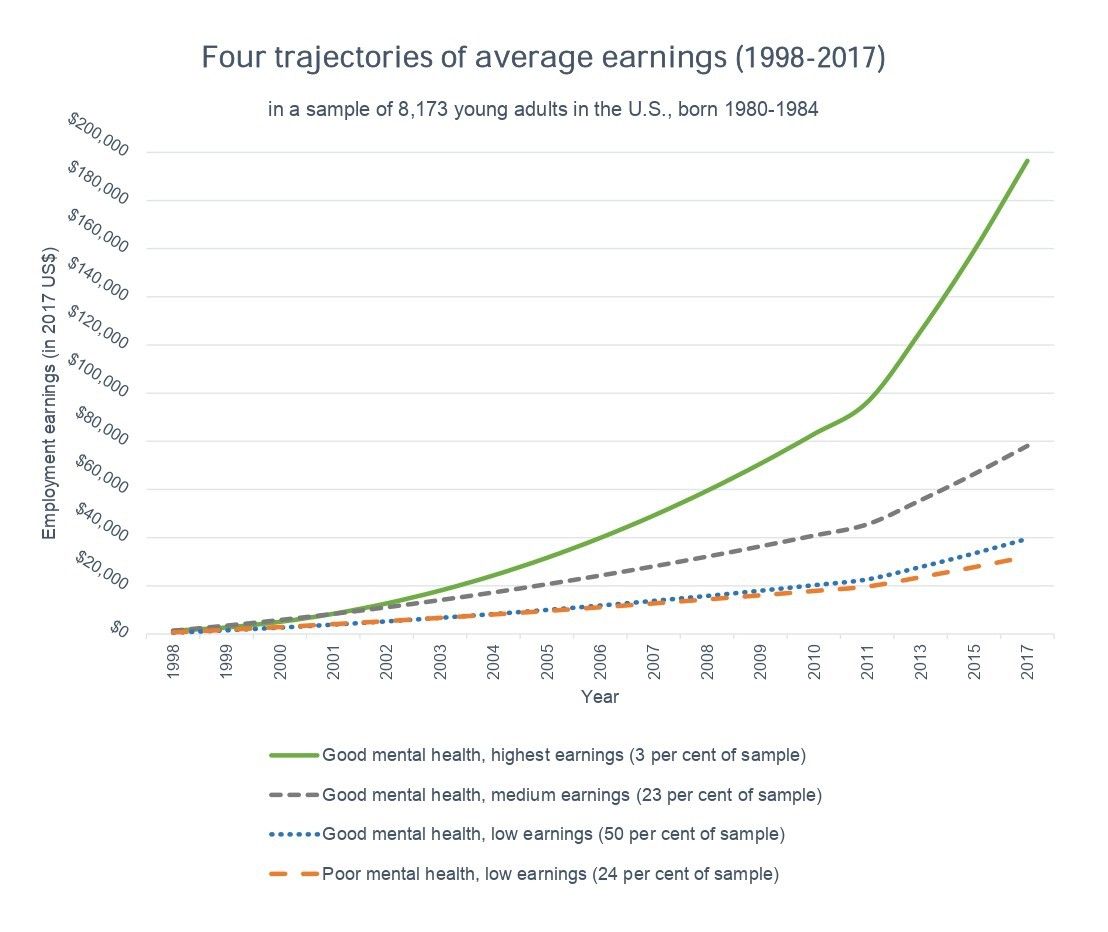

When it comes to earnings, all groups had increasing earnings over time. However, the group with the poor mental health scores was also the group with the lowest earnings. By the time they were in their mid-30s, individuals in this group made about US$32,000 a year. Of the three remaining groups (all with stable, good mental health), those in the highest earning group, representing three per cent of the sample, made nearly US$200,000 a year in 2017. Those in the medium-earning group, representing 23 per cent of the sample, made US$78,000 a year. And those in the low-earning group, the most populous one with 49 per cent of the sample, made US$40,000 a year by the time they were in their 30s. The average earning of this last group was closest to the average income of US$42,000 a year for workers aged 25 to 34, according to the US Census Bureau, notes Dobson.

While emphasizing that the findings cannot speak to whether poor mental health leads to poorer earnings or vice versa, “they do offer us a picture of how mental health and earnings move concurrently together,” says Dobson.

Four groups and their characteristics

After Dobson identified the four groups, based on the four earnings-and-mental-health pathways, Dobson’s study sought to examine their characteristics. “We wanted to know what factors measured in the 1997 baseline survey were associated with the odds of being in one of these groups,” says Dobson.

Out of a broad range of demographic, socioeconomic and health-related factors measured at baseline, a few stood out as the strongest predictive factors. Being female, Black or Hispanic was strongly associated with higher odds of being in the group with poor mental health and low earnings, while having high parental income and net worth at baseline was associated with lower odds of being in this group.

The factors that we saw were predictors of belonging to the poor-mental-health-and-lowest-earning group are known risk factors of common mental disorders, at a population level. We also know that, at a population level, these factors are associated with lower access to the labour market and to higher-paying jobs over time.

Dobson says.

However, what we found surprising is how strong the associations were.” As an example, she notes that study participants who were female had 3.2 times higher odds of belonging to the group with poor mental health and low earnings, when compared to the group with good mental health and medium earnings (the one with US$78,000 in average earnings in 2017). Black participants had 1.7 times higher odds of belonging to this poor-mental-health-low-earnings group, and no statistical differences were found for Hispanics. These differences were even greater when compared to the good-mental-health-high- earnings trajectory.

Dobson also emphasizes the importance of viewing results through an intersectionality lens. This study was not designed to prove causality,

she says. Nevertheless, the interactions between one’s social environment and sociodemographic characteristics can lead to different health outcomes and work experiences that may continue to impact each other over time. Although this study can’t untangle this, it is a first step to guide future research and policy.

Key takeaways

Mental health is not always easy to research in longitudinal population studies focused on labour market indicators. One of the more notable findings of this study was the long-term stability of participants’ mental health scores. Dobson notes that mental health in this study was defined more broadly than the clinical measures of major depressive disorders and psychological distress often used in smaller studies. In the survey, participants were asked, in the previous month, how often they had been a very nervous person; felt calm and peaceful; felt downhearted and blue; been a happy person; and felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer them up.

If a more clinical or diagnostic measure were used, it is possible that we would have seen more variability in mental health than what we have here,

adds Dobson. Indeed, in an upcoming paper that also looks at trajectories of depression based on clinical measures, Dobson and her team do find evidence that trajectories may fluctuate over time.

Dobson notes, as well, that the stability of the mental health scores does not undercut the value of support programs and interventions. The finding that poor mental health in adolescence may be associated with poor mental health and lower earning across the lifespan points to the need for early interventions and support programs—especially those aimed at providing ongoing education and skills training opportunities, and increased access to counseling, treatments or other therapies to reduce the impact of depression on social mobility and help young adults move out of poverty,

says Dobson.

Also important is that activities should not put all the onus on young adults with depression. These efforts should be complemented by programs focused on raising awareness about the long-term social, economic, and health effects of suboptimal mental health in adolescence, the need for programs to help young adults return to their studies after periods of absence, and ways to enhance education and skills building,

she adds.

How the study was done

The study was conducted using the U.S. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, a complex, longitudinal survey that offers “data at a level of detail not found in Canada,” says Dobson. The survey is administered every year from 1997 to 2011, then every two years until 2017. The initial sample, consisting of 8,984 individuals born between 1980 and 1984, aimed to be representative of this age group in the U.S. population. The survey also purposefully recruited more Black and Hispanic youth than their percentages in the population.

As mentioned, the mental health scores were based on five questions that asked participants how often they had been a very nervous person; felt calm and peaceful; felt downhearted and blue; been a happy person; felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer them up. These questions were asked every two years from 2000 (except for one five-year interval between 2010 and 2015). Questions on earnings were asked yearly and figures were converted to their 2017 value.

With a final sample of 8,173 (after participants who did not meet the sample criteria were removed), Dobson’s team mapped pathways for each individual in the study. Using statistical modelling methods, the team created groups of participants who had similar mental health and earnings trajectories. When doing so, Dobson’s team had to balance the need to capture patterns that were common enough that they were likely not due to chance and the goal of being as sparing or parsimonious as possible in their model. As for next steps in her research, Dobson says “continuing to study what factors or interventions help individuals with mental health challenges succeed in the labour force is critically important to ensure that this group of individuals can thrive in the workforce.