Much has been written about the distinguishing features of workplaces that have a strong health and safety record. But what distinguishes workplaces that turn around a poor occupational health and safety (OHS) performance? What can their success stories tell us about the critical factors for breakthrough change?

That was the focus of research behind the development of a new resource from the Institute for Work & Health (IWH), a series of case studies that illustrates a research-based model of the breakthrough change process. We know that people like to learn through stories, and they prefer to read about workplaces similar to theirs,

says Dr. Lynda Robson, a scientist at the Institute and lead researcher on the project.

We hope these case studies will inspire others to make large improvement in their workplaces and give guidance on what might help the process,

adds Robson. She suggests workplaces use these case studies as the basis for discussions and brainstorming among management teams, OHS departments and joint health and safety committees about ways to make large and sustainable improvements in health and safety.

In this research, Robson took a novel approach by starting with an outcome of interest—large improvement in OHS performance—and then seeking the story behind that improvement. What did the workplace do? Why? Who was involved?

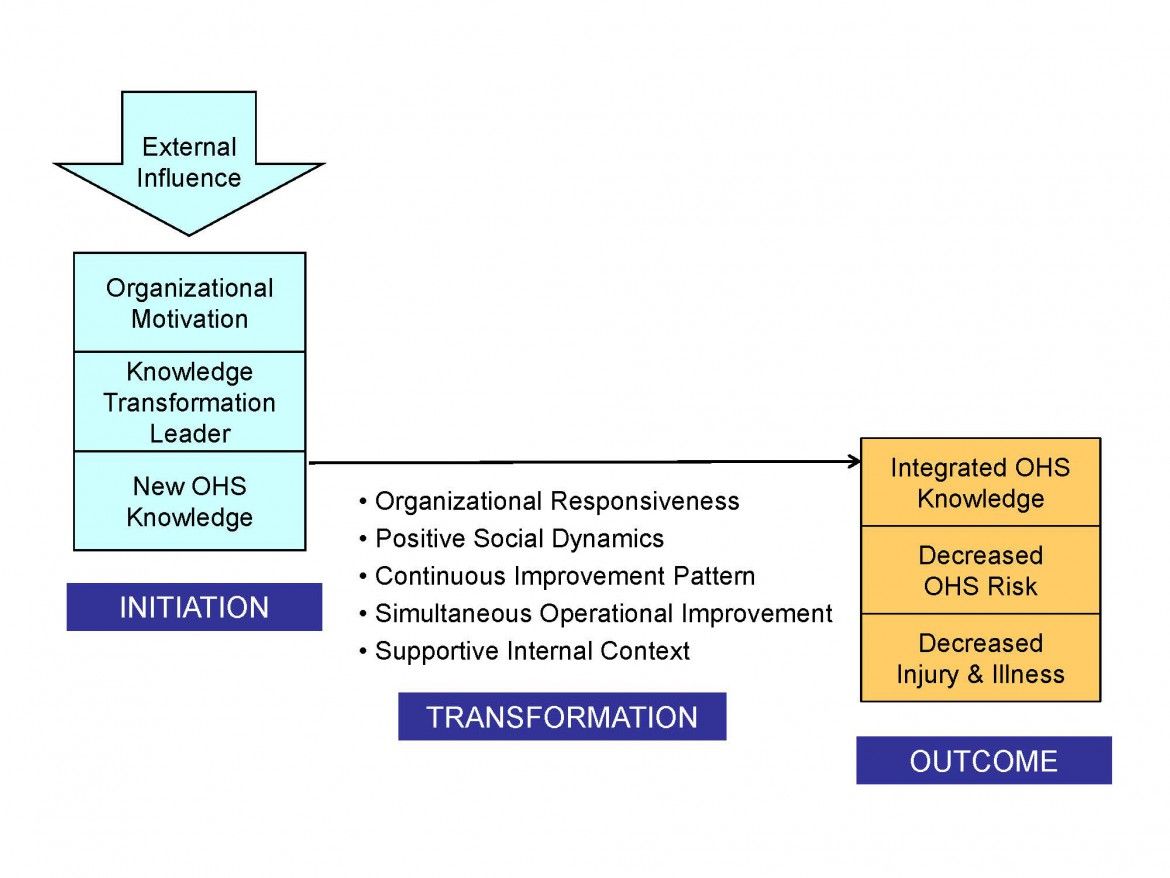

She ended up taking a close look at four workplaces: a discount grocery franchise, a plastics manufacturer, a metal product manufacturing plant and a community agency operating several group homes. (For more on how the research was conducted, see the Spring 2014 and Fall 2012 issues of At Work.) From the accounts put together of the process of change at each organization, Robson and her team identified common key factors to build a model of breakthrough change (see model).

Four common factors initiate change

Although the details may differ, the process of change at all four workplaces began when the same key elements were in place. As shown in the model, the critical factors at this initiation phase are: (1) external influence; (2) organizational motivation; (3) new OHS knowledge; and (4) a knowledge transformation leader.

External influence, in the four case studies, ranged from intervention by the provincial labour department to a shift in customer demand. At the group home agency, for example, a health and safety association consultant’s offer of assistance helped management recognize that the agency’s OHS performance was subpar and needed to improve, as part of its pursuit of excellence. At the grocery store, the light went on when franchise owner John heard of a serious injury involving a young worker at another grocery store. That incident prompted John to reflect on the number of young people he was employing at his own store and the risks they faced. He realized he needed to get a health and safety program up and running, and that he had to bring in outside help to do so.

A new source of OHS knowledge was another critical factor setting change in motion. In the case of the grocery store, the external consultant not only helped develop the health and safety manual as well as health and safety forms, she also rejuvenated the JHSC by providing members with information on legislative requirements and other OHS news in the industry.

Another important factor was an OHS champion, called a knowledge transformation leader in the model. This champion was an important component in all four case studies. Whether the person had the title of human resources manager, health and safety co-ordinator or owner, his or her contribution was remarkably similar. He or she orchestrated the transformation of OHS knowledge from being external to the organization to being integrated into the organization as new policies, structures, procedures and practices for both managers and workers.

To bring about this change, the knowledge transformation leaders used their strong skills in both administration and dealing with people,

says Robson. This skill set is something senior managers might want to keep in mind if selecting a person to drive improvement in OHS in their workplace—whether hiring a new employee or assigning new responsibilities to a current employee,

she adds.

(For more about the role of the health and safety champion in breakthrough change, see the Spring 2014 issue of At Work.)

Integrating new OHS knowledge

Once the process of change had been initiated, several factors came into play to help the organizations integrate new OHS knowledge in practices and policies. As seen in the model, the factors include: (1) organizational responsiveness to worker OHS concerns; (2) positive social and psychological dynamics; (3) a continuous improvement pattern; (4) simultaneous operational improvement; and (5) a supportive internal context.

The most remarkable among these was positive social dynamics, which the team saw right across all four case studies. There were stories of good rapport, strong collaboration, individual development and empowerment. The concept of positive social and psychological dynamics was not on our radar going into the study, but it emerged strongly from the research data,

says Robson. For example, people talked about the joint health and safety committee developing the right energy.

Another common factor was responsiveness to the OHS concerns of employees. In the case of the metal products manufacturer, for example, the new health and safety co-ordinator made a point, soon after she joined, of finding out from workers what health and safety issues concerned them. She quickly acted on those issues and, in doing so, helped create a virtuous cycle of people speaking up more and expecting more on OHS issues. A similar phenomenon was seen at the plastics manufacturer, where the maintenance department acted quickly on workers’ concerns, becoming a “catalyst” for further participatory change.

The “internal context” of the workplace was important too. In all cases, senior management supported the OHS improvement, even though the senior managers were not usually involved in a hands-on way. As well, management-employee relations were generally good. Another factor was the concurrent effort at these workplaces on operational improvement—for example, by adopting “lean” manufacturing methods.

A final factor was the pattern of continuous improvement seen in all cases. These workplaces had an attitude of “what’s next?” and continued to make changes over time. For example, after the grocery owner got his program off the ground, he continued to have the external consultant meet quarterly to pass on new information to the JHSC. At the plastics manufacturer, new objectives were set each year, some similar to previous years and others reflecting further innovations on OHS.

A ‘good resource’ for leaders

Though noting that this model is built on a small sample of four case studies, Robson has found that it resonates with the OHS practitioners she has spoken to. For Candice Brown, safety and injury management advisor at the British Columbia Construction Safety Alliance, a safety association funded by the province’s construction industry, the capsules are “a good resource for someone in a leadership position, or health and safety professional, to take to the management team.”

They outline very nicely the process and benefits of change, and seeing that process in stories really helps in building a business case to enable initiation of change,

she says.

They are also a good learning tool for leaders, to help them think through: How will we initiate change? What steps do we need to take? How will we motivate and engage people in all levels of the organization to make any changes successful?

Robson is now exploring further how breakthrough change takes place, by looking at workplaces that were similar to the four cases before their breakthrough change, but did not undergo large and sustained improvements in OHS.

We are finding that the factors of initiation and transformation from the breakthrough model are not present to the same extent in these comparison cases,

she says.

To download the case study capsules, go to the tools and guides page. This project was also the subject of a plenary held in May 2014, a slidecast of which has been posted on IWH’s webpage and YouTube channel.