Why is deciding whether to share support needs at work so difficult for people with a chronic health condition?

The reasons are many and they are complex.

They include uncertainty around the outcome of discussing support needs at work. People might be concerned about stigma, gossip, the potential damage to their reputation or the potential impact on their career advancement. They might be worried about losing their job if they disclose—or losing their job if they don’t disclose.

For individuals with episodic health conditions where symptoms come and go, a decision to disclose may not be a one-and-done event. As they experience changes to their health, their job demands, their manager or work teams, whether to share health information is a decision that people may have to make over and over again.

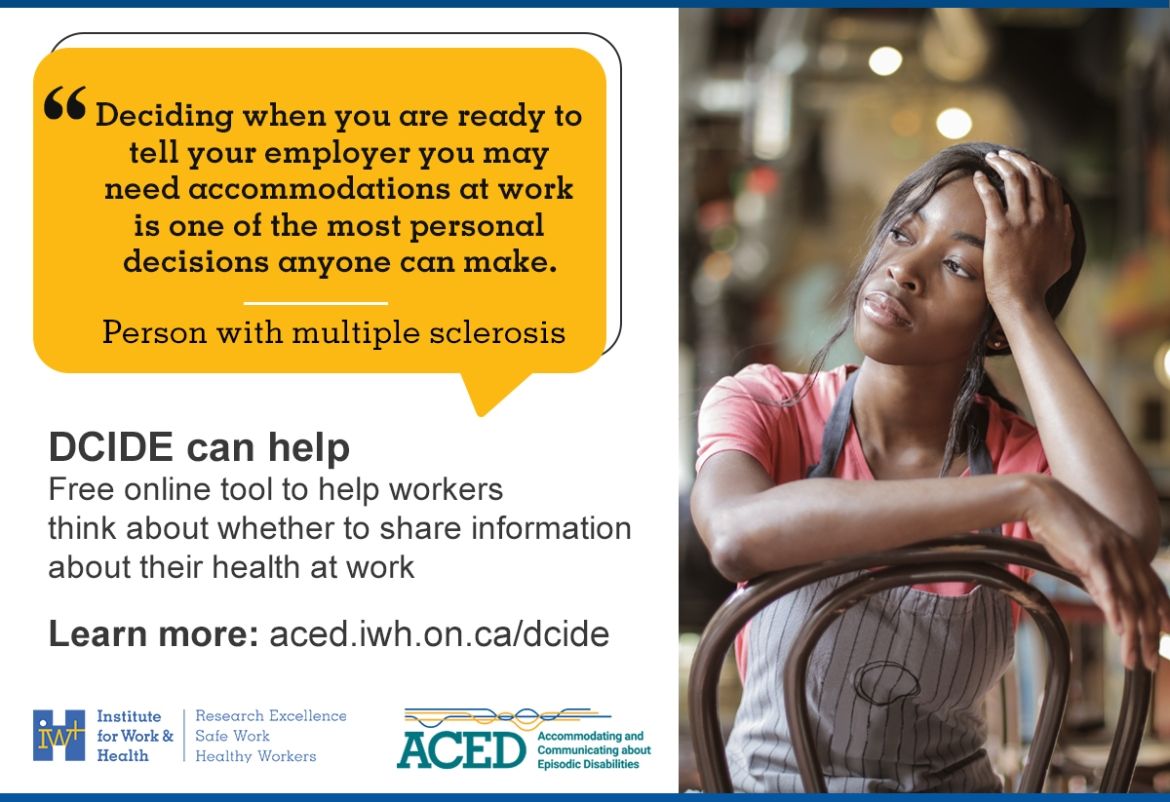

Whatever factors they take into consideration and however they decide, the act of making a disclosure decision can be complex. That’s why a team at the Institute for Work & Health (IWH) has developed an evidence-based tool called DCIDE—short for Decision-Support for Communicating about Invisible Disabilities that are Episodic.

The aim of the tool is to help people think about different aspects of a decision to share personal information at work, so that they can feel more confident that they are making a decision that’s right for them,

says Dr. Monique Gignac, IWH senior scientist, at the November 2024 Speaker Series presentation where DCIDE was launched. Gignac leads the Accommodating and Communicating about Episodic Disabilities (ACED) project, which resulted in the development of DCIDE, as well as a companion tool called Job Demands and Accommodation Planning Tool (JDAPT).

DCIDE, which is free to use and available in English and French, takes users through five different sections, related to different areas that are important to consider when making a disclosure decision. These are:

- their needs;

- their goals;

- their communication and sharing preferences;

- their work support availability; and

- their work culture.

These five areas have emerged in research as the ones most pertinent to workers when faced with this decision. After completing each of the five sections, which will take most people about 15 minutes, the worker gets a tailored summary to help guide them in their decision whether or not to disclose. The tool also provides tips and resources to help them in the next steps after making their decision.

The DCIDE tool can help people think about whether to talk to people who are most likely to be able to provide support—e.g., a supervisor, a human resources manager or a disability manager. People can also use the tool to consider whether to share their health information to a co-worker or a union representative.

Ideally, people would use DCIDE alongside the JDAPT,

notes Gignac. The JDAPT is a free online tool that helps workers with episodic disabilities find practical solutions for their job demands. It guides users through questions about their work tasks and conditions, and provides personalized suggestions for support and accommodation. Once they’ve used DCIDE to consider whether they would disclose their health condition, they can turn to the JDAPT for ideas of support and accommodations that they can ask for or implement on their own,

Gignac adds.

Perceptions matter

In her presentation, Gignac shared findings from a study that examined patterns of responses in a sample of 600 workers who tested out the tool before its formal launch. In this study, participants were asked to complete the tool and to provide additional information, including demographic characteristics and workplace characteristics. Importantly, they were also asked about the stress they experienced when making a decision about whether to share information about their health condition, whether they felt forced into a decision, whether they had enough information to make a good decision based on their circumstances, and whether they had disclosed previously to a supervisor, co-workers, or others at their workplace.

The study aimed to understand the tool’s ability to identify different decision pathways and to meaningfully differentiate among them. Study findings also provided the project team with some insight into what users thought about as they used the tool.

The research team found that objective factors such as whether people had supports available at work or whether they experienced health issues were not always the primary factors that shaped people’s disclosure decision. Over a third of study participants had significant health needs as well as available supports, but they were either very reluctant to disclose or uncertain about sharing information,

says Gignac. For these individuals, their goals and perceptions of their workplace culture were important considerations, she notes.

Our message to workplaces, as a result, is that workers’ subjective perceptions often take priority when they decide whether to disclose. These perceptions can be as or more important than what a workplace says it has available in their policies and practices,

says Gignac.

Even if an organization has the policies in place to provide accommodation, the work is not done,

she adds. Supervisors and managers within the organization still need to make sure to foster a supportive workplace culture so that employees will feel less reluctant and more confident about asking for help. Not all workers will be comfortable sharing personal information and finding ways to recognize this when implementing support policies is important.

A worker’s perspective

For former registered nurse Amanda Fraser, whether or not to disclose was not a choice she could make. She was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) at the same hospital where she worked, so everybody knew I had MS before I had the chance or the time to disclose.

The experience left her feeling like she was “pigeon-holed” and led to her going off work earlier than she felt she expected to. If I had a tool that helped me think about how to share my health needs, I think I could have remained at work longer,

says Fraser.

Now that she has had an opportunity to use tools like DCIDE and JDAPT, looking back, I think I could have asked to alter my hours and do eight-hour shifts instead of 12,

she adds. I could have asked to move to an area in the hospital where I was not on my feet as much. I could have gone to outpatient care or somewhere that’s slower and less stressful

than the wing she was on, Fraser says.

The important thing to get across is I didn’t know how to advocate for myself. I didn’t know what questions to ask or what accommodations to ask for. That’s why I think these tools are so important.

As one of the expert advisors on the DCIDE team, Fraser drew on her lived experience to provide feedback to help make the tool useful and relevant to others with chronic health conditions.

Tools like DCIDE and JDAPT can empower people to take their health care and their choices into their own hands and learn what accommodations to ask for,

says Fraser. The tools can also help managers and supervisors consider workers’ perspectives when facing a decision to disclose and gain ideas about available accommodation, she notes.

You don’t need to have all the information about someone’s health,

she adds, addressing managers and supervisors. You can just know that something’s going on and provide help without requiring full disclosure. There are ways to accommodate people other than putting them on long-term disability.