Returning to work after an injury can be challenging for employees in any sector. But one sector prone to unique and complex work-related injuries—policing—has its own set of return-to-work (RTW) challenges.

Police service members are exposed to a variety of hazards in their work which can lead to injury and illness. While physical injuries are substantial, mental health injuries and post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) are also gaining increased attention. According to research conducted elsewhere, the prevalence of PTSD ranges from eight per cent reporting symptoms in a 2009 sample of Canadian police officers to 23 per cent reporting symptoms in the previous month in a 2016 sample of Canadian public safety personnel. Such findings highlight the need to ensure supports are in place for police members who are recovering or returning to their jobs.

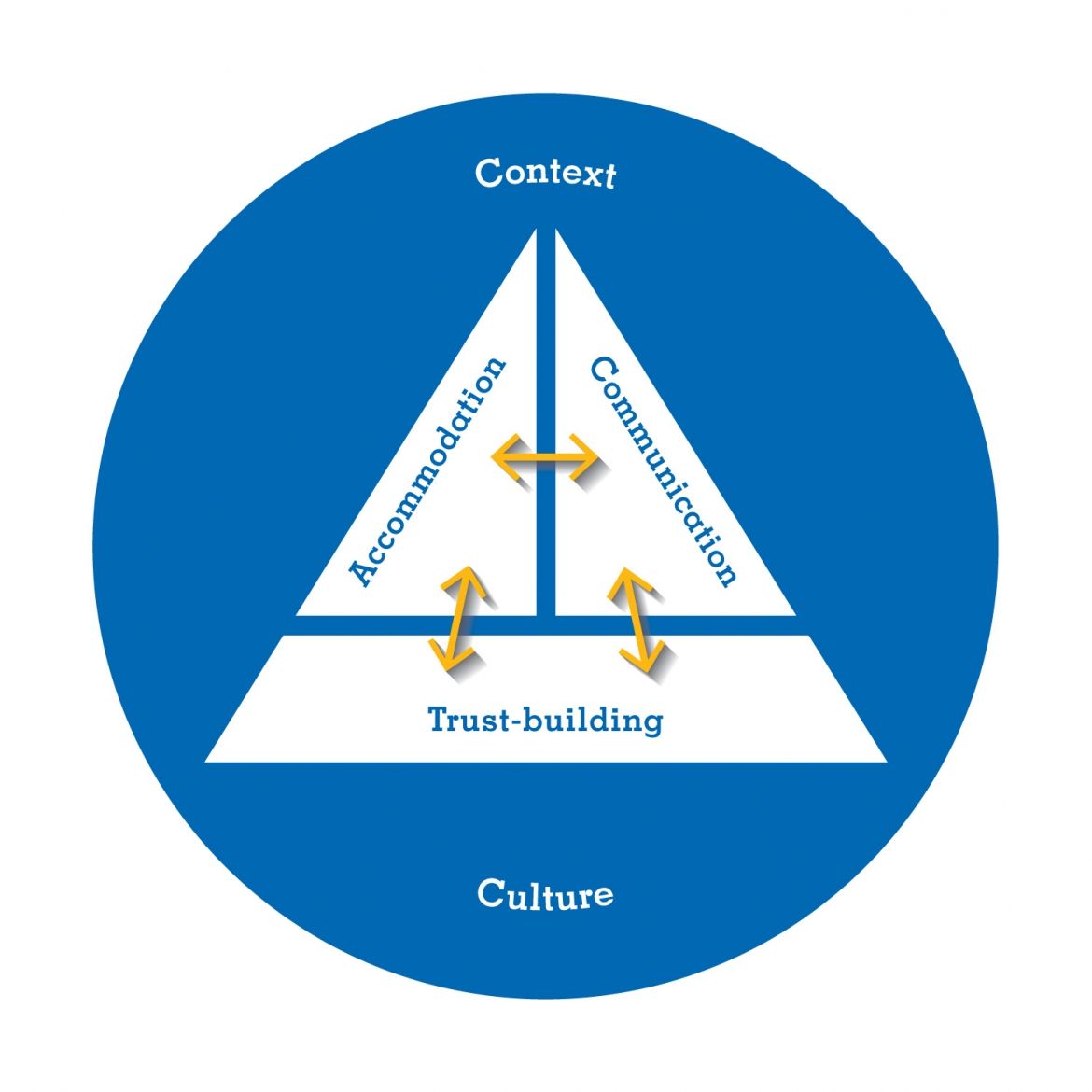

In a recent study by the Institute for Work & Health (IWH), published as an open access article in September 2023 in the Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation (doi:10.1007/s10926-023-10135-1), Scientist Dr. Dwayne Van Eerd and colleagues found that RTW challenges faced by sworn and civilian Ontario police service members revolved around five main themes: context, culture, accommodation, communication and trust-building. Additionally, police were often prone to complex, psychological injuries such as PTSD, or had both physical and psychological injuries, and RTW challenges were often amplified in these situations.

Challenges were identified by conducting 49 interviews with sworn and civilian Ontario police service members who had returned to work after an injury, and members involved in facilitating that RTW process like disability managers. The sample was chosen to purposely include employees across a broad range of experiences with RTW processes, roles, genders, and types of work-related injury. The research team worked closely with a stakeholder advisory committee made up of members from police services and police associations. Members of the committee helped recruit interviewees, ensure proper terminology was used in interviews, and develop the key messaging arising from the results.

The first two themes that arose from these interviews, context and culture of the workplace, were shown to contribute to the challenges outlined in the other three themes, accommodation, communication and trust-building.

Context. Context plays a key role in shaping RTW experiences. In particular, participants noted that policing is a service essential to public safety and felt that this had an impact on RTW practices. They also spoke about the nature of the injury, whether physical, psychological or both, as an important contextual factor.

Culture. Aspects of the police service’s culture, such as hierarchy or chain of command, were also seen to affect the RTW experience. Interviewees often noted that those with work-related injuries were referred to disparagingly as broken toys

. Stigma about injuries, particularly psychological injuries, were reported as hindering the return-to-work process if it caused members to delay seeking treatment or returning to work,

Van Eerd notes.

The following three themes were thought to be shaped by aspects of the context and culture of returning to work within the police service. Van Eerd describes them as key areas of focus to ensure a successful RTW transition.

Accommodation. Van Eerd notes that members’ varied recovery needs and accommodation requirements upon their return to work, particularly for complex and/or psychological injuries, were an important, but challenging, consideration. Many interviewees were worried about being able to perform well in their previous job or being seen as weak or damaged because of an injury. As Van Eerd puts it, it is challenging to find available positions in perhaps any workplace to accommodate medical restrictions. But if, for example, public-facing duties are off the table for a police officer due to an injury, it is challenging to find a new role that feels as meaningful for them. What usually happens is that they’re moved to a desk job. And as we commonly heard among some interviewees, sitting behind a desk doesn’t feel as meaningful.

Communication. Another common issue involved communication around the RTW process. The people we spoke with who had experienced an injury did not have a strong sense of how the return-to-work process worked. Many had difficulty finding information when they needed it,

says Van Eerd.

An additional challenge for those with psychological injuries was a reported need for balance between receiving enough communication to have relevant information and paperwork, but not getting too much that it’s overwhelming – particularly when injuries may make concentrating and processing information more difficult. Some participants also were reluctant to share information about their injuries with others, being concerned about gossip and stigma impacting their future career. This also related to the final theme in the study, trust-building.

Trust-Building. Van Eerd noted that the need for trust-building was another area of concern when returning to work. A number of people we spoke to mentioned what they described as a well-known lack of confidentiality within the police service,

says Van Eerd. Some interviewees reflected on stories of their injury status being shared with co-workers or other employees without their consent. In general, there was a distrust of human resources. There was a fear that if they divulge or take time off work for certain injuries, they wouldn’t be considered for promotions or new positions,

says Van Eerd. Again, confidentiality concerns were often greater for those with psychological injuries.

Some interviewees also noted that injured members had been falsely accused of malingering, i.e., pretending to be injured or for longer than necessary in order to cheat the system

and continue receiving support or time off. Interviewees noted that this misperception can cause an injured employee to not report an injury or even delay returning to work.

Takeaways

These challenges suggest the importance of clear and non-adversarial communication about the RTW process. Such a process should include injured members in considering appropriate accommodation, focus on providing meaningful work upon their return, and, crucially, consider members’ different communication preferences. Furthermore, the research findings suggest that ensuring confidentiality, using non-stigmatizing language, and eliminating the framing of injury as weakness may help improve the RTW process and reduce misperceptions around workplace injuries in the police service. For a full list of suggestions that arose from the findings of this study, check out the Time to ACT resource.

Van Eerd is a project team member on a new IWH project aimed at providing telementoring to care providers who treat or support public safety personnel with mental health injuries. The ECHO Public Safety Personnel (PSP) starts weekly sessions in September 2023 and is now open for registration. To find out more, go to: https://echopsp.iwh.on.ca/